If you ask manufacturers what’s shutting down their supply chains and driving market-wide silicon shortages, 9 out of 10 will point to COVID-19-based factory closures. But parts are delayed for 52 weeks while factories were closed between 2–6 weeks, so what was the real reason? A deeper investigation shows that a growing combination of trends seen in the past, like tight lean raw material inventory management and the bullwhip effect, are largely to blame.

In 2018, something strange began to happen with MLCC capacitors, a commoditized and extremely common type of ceramic capacitor used in most electronics. Prices began to double and triple. The parts couldn’t be found anywhere on the market. Businesses were in shock, and the iPhone X was out of stock quicker than consumers could hit the “buy” button. COVID-19 had never infected anyone at this point, and “social distancing” was practically unheard of. So then, what changed?

The 2018 shortage started with a supply shock, much like the shortage we face today. The automotive industry was moving to add electronics to cars at rates much faster than forecasted, and capacitor capacity couldn’t keep up. In consumer electronics, MLCC use was going up as well. Apple’s new innovative Iphone X had just released to staggeringly high demand while it’s MLCC count jumped up from 500 to 1,000 capacitors per set, greatly increasing the amount of materials needed for production. Capacitor factories require time to set up and require millions of capital investment. When demand skyrocketed, the industry had little to no time to catch up.

Manufacturers focused on lean inventory management, only ordering the necessary quantities of raw materials to meet expected demand with little reserves. This works great in theory, but in times where traditional supply chains are stressed, like the pandemic this year, the problem finds the space to rear its ugly head. In 2018, these factories held inventory positions of only 8 weeks of stock so when lead times went up by a month or two, lines went down. Manufacturers learned a hard truth — a single part valued at less than $0.01 can halt a multimillion dollar product line in its tracks.

But that’s not all that happened. Enter the bullwhip effect. Triggered by increasing demand and worried by longer lead times, the electronics industry reacted. Most companies bought up to 10x their typical purchases to stock up. In the case of the MLCC shortage, this dragged supply issues out for 18 months, well beyond the natural timeline to handle the bubble.

Today’s shortage displays the same fundamental DNA. A supply shock due to COVID closures, a lack of resilience due to lean raw material reserves and the bullwhip effect in overdrive. Now the most renowned manufacturers are in trouble. According to Sony’s CFO, the world-famous Playstation 5 will most likely remain in shortage through the end of 2022 due to electronic component planning, leaving a two year gap in profitability for one of the most universally reputable companies around. Even the auto industry is expected to suffer from shortages and will produce 1M fewer cars than was forecasted at the beginning of the year, while concurrently suffering more than $110 billion in revenue.

Lean raw materials inventory management fundamentally fails under supply shocks like the current one. Lean manufacturing puts an unreasonable amount of pressure on suppliers to be flawless in their delivery on short notice. More critically, it assumes that only customer demand for finished goods will vary, not the lead time of parts. Lengthening lead times cause the whole system to crumble under pressure. To add insult to injury, manufacturers are often forced to pursue parts from untrustworthy suppliers to avoid falling short of demand.

Global trends seem to indicate that the variability of raw material lead times will only get worse. Tariffs, increasing China and US tensions and shortening product cycles are all worsening the effect. So is lean raw material inventory management dead?

Lean raw material inventory management needs a facelift to account for risk in the market. Factors like shortage indexes, open market part availability, popularity and criticality of the parts should all be combined to create standard deviations on part lead times similar to how we forecast customer demand. The COVID pandemic has merely revealed the issues with the current inventory management approach, and manufacturers are being forced to improve.

Want to see if your manufacturing network has the scarce parts you need?

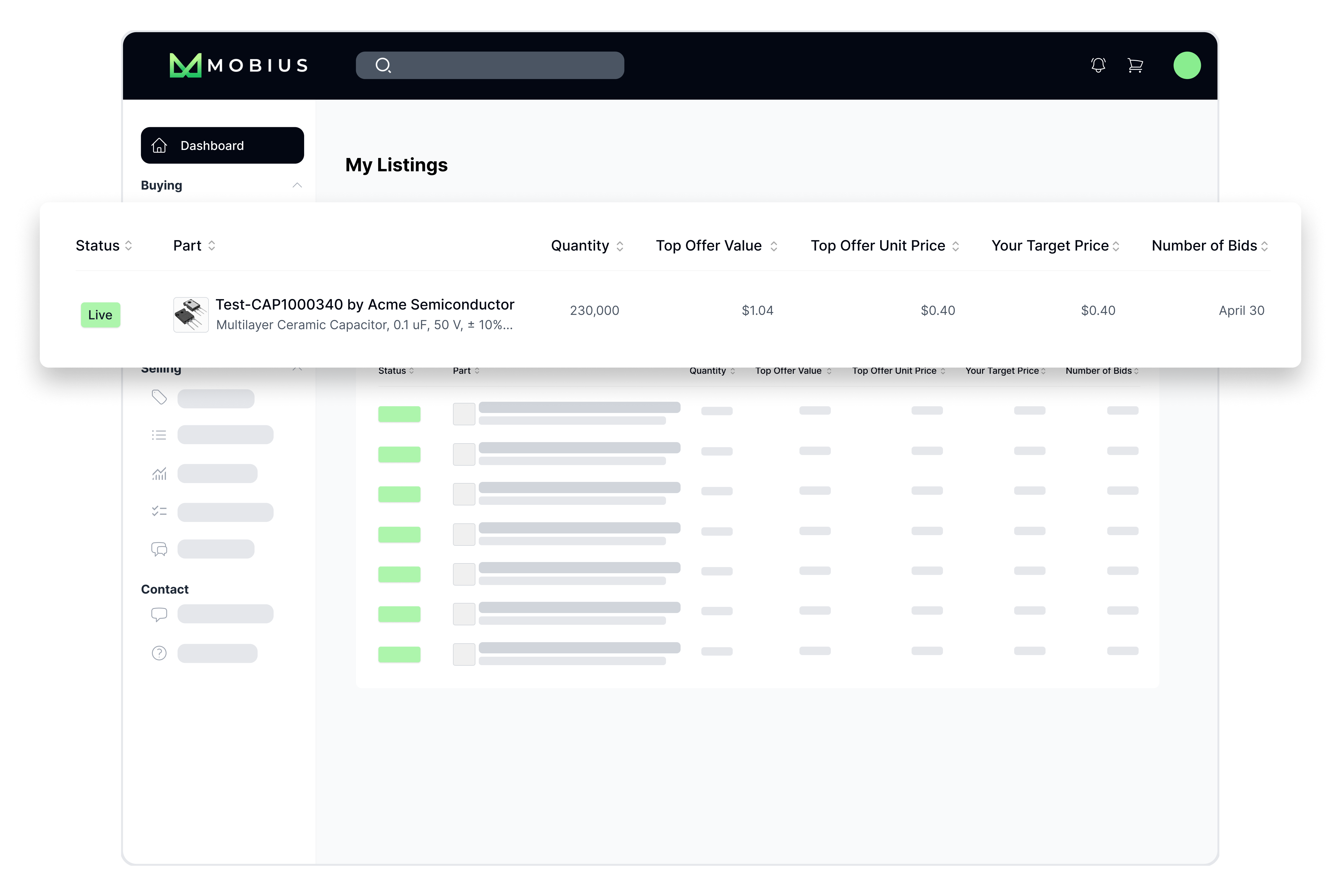

San Francisco startup Mobius Materials has found an opportunity for businesses suffering amidst this problem. As the company’s founder Margaret Upshur discovered, manufacturers typically have excess electronic components that can be sold but are not ultimately reducing environmental footprints and increasing profit margins. Mobius is an ever-evolving hub and marketplace for manufacturers to trade their vetted excesses among themselves, and keep track of the status of their valuable components. In other words, even during year-long shortages and turmoil, efficient innovation has allowed for your business’s trash to become another business’s treasure.

Check out more blogs, a custom-built shortage tracker, and our marketplace here; https://app.mobiusmaterials.com/shortage?utm_source=Medium&utm_medium=organic&utm_campaign=wwn

Works Cited:

Topic: Global chip shortage 2021

Active Electronic Components Market Size Report, 2021–2028

Prices and lead times are at an all time high. Based on Mobius’ market observations, a single part that normally sold at a reasonable price can now be found priced anywhere from 2–8 times its original price.

https://www.theverge.com/2021/4/15/22385261/nvidia-gpu-shortage-rtx-3080-warning-comments-2021

https://www.reutersevents.com › supplychain › end-just…

FT: Carmakers must ‘put money on table’ to avoid repeat of chip crisis